“I have no problem with gay or trans people—as long as they don’t force their beliefs/lifestyle/opinions onto me.”

-a clueless heteronormative, probably.

Maybe you’ve heard of Florida’s Republican-led “Don’t Say Gay” bill, attempting to restrict discussion around gender and sexuality in schools. Or the USA Supreme Court’s decision to strike down affirmative action in college admissions, subsequently pushing pack non-traditional progress narratives, such as those which allow historically marginalised groups to access institutions via alternate routes.

Someone might argue the case that “A heteronormative society should be accepted as default—and if queer people want to be accepted, they should act like everybody else.”

Except…this is an impossible expectation to uphold. In a heteronormative society, a queer experience will always grow and evolve differently to straightness.

ENTER: Queer Temporality.

“Stemming from the work of queer theorists such as Lee Edelman, Jack Halberstam, Jose Esteban Muñoz, and Elizabeth Freeman, queer temporality calls for reconsideration of how marriage, children, generativity, and inheritance define and confine cultural expectations of maturation, responsibility, happiness, and future.” — Oxford Research Encyclopaedia

In a nutshell, queer temporality describes the phenomenon of how queer and straight people move throughout time according to different timelines. For instance, while a cisgender timeline develops around biopolitical goals such as conception, childbirth and child-rearing, their transgender companion intrinsically disrupts this normative model of time: the moment of transition fractures a normative cisgender progression of childhood and adolescence, as well as delaying time for the post-transgender body who now has to catch up on new gender experiences that could not be actualised pre-transition.

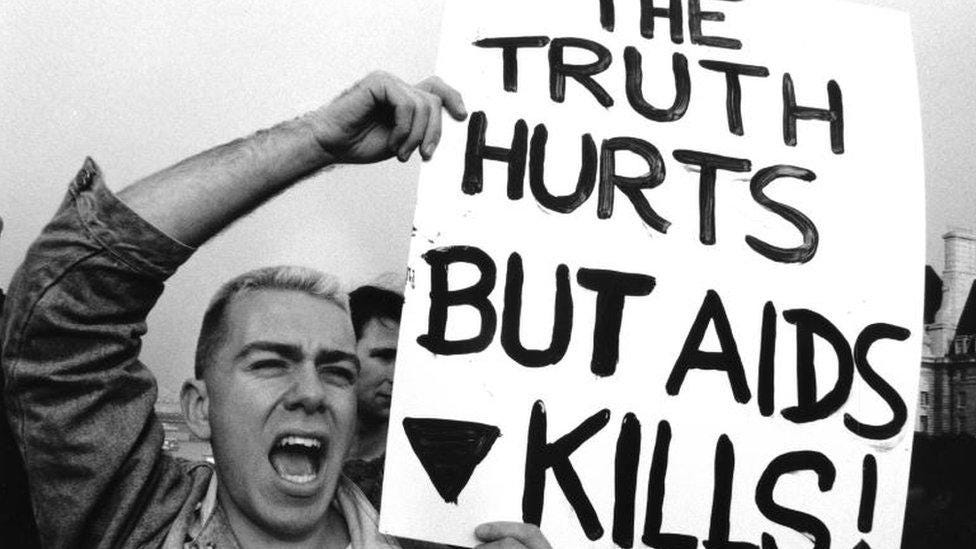

Queer theorist Jack Halberstam argues the AIDS epidemic, emerging from the 1980s, was the biggest factor which pushed queer time into existence as its own space, undefined by straight temporality. The death drive which emerged as a product of the AIDS crisis pressurised queer spaces to self-define and break away from the heteronormative timeline, since the threat of a fatal disease—itself associated with queer expression and love—limited the possibility of aging, and having time to fulfil the biopolitical goals outlined by a heteronormative timeline.

The examples of the political war on queerness in modern USA I provided above showcase queer temporality in action. The “Don’t Say Gay” bill attempts to erase queer identity, history, and experience entirely by stifling conversation about it. This delays a Floridian queer child’s adolescence significantly, forced to explore their own sexual identity and self-expression much later than their straight peers.

Similarly, dismantling affirmative action demands that academic success adheres to meritocratic standards, further benefiting the already-domineering factors of whiteness, maleness, and straightness.

So it seems that measures are being established by straight/cis people to push queer people back into the heteronormative mould of time we’ve seen for the entirety of history, not the other way round.

Let’s apply this theory to the past—A Historical Detour

In 1829, a book was created, publishing the dictated confession of a AFAB Nun who lived and identified as a man. Lieutenant Nun: Memoir of a Basque Transvestite details the life of Antonio, whom escaped a convent and ended up living as a colonial soldier in their attempts to conquer South America during the 1600s*.

( *It’s worth noting Antonio’s (potentially) queer experience is privileged by their whiteness and existence on the “white-saviour”, colonial side of history. More on that later.)

If the concept of being trans, or anything other than cis, is widely considered to be a 20th century concept. Thus, transgender time throughout history is ambiguous to define—especially considering Halberstam goes as far to define the transgender body itself as post-modern in A Queer Time and Place.

I’m reluctant to apply the term ‘trans’ to Antonio, both to avoid presentism and also because I can’t speak for a real person who didn’t have the knowledge nor words to self-define in this way. Regardless, the conscious choice to live as male-presenting and to assume male gender roles in a deeply Catholic, patriarchal society is profoundly interesting.

As it is written as an auto-biographical memoir, in Lieutenant Nun, Antonio has some degree of agency over defining their own identity.

Eastwood comments on Transness and self-authorship, ‘literary history offers an alternate perspective on how trans people experience and reinterpret history, as authors and as readers’

Eastwood implies that the form of literature enables an accurate depiction of transgender history, as gaps in time and ambiguities lend room for a queer interpretation. However, in Antonio’s case, it is unknown firstly if they wrote it personally, and secondly, how heavily their confession was edited posthumously (for instance, in order to reduce the scandalous content). If, for example, they dictated this story to a professional writer or secondary party, their trans voice would have been filtered through a cisgender narrative, complicating the purity of their authentic experience. Furthermore, this memoir was created solely to be used as a confession and remained unpublished for 150 years, reminding the modern reader that Antonio did not intend to depict immortal evidence of the trans experience.

Whilst heteronormative time is seen as ‘‘productive’’ in its pursuit of fulfilling biological markers, queer time is often categorised as ‘‘selfish’’.

For example, spaces where the queer experience is most saturated include the ‘‘selfish’’ time of:

Voluntary childlessness**.

Promiscuous time or times of sexual expression.

‘‘Junk Time’’, as first defined by Burroughs in Junky (1997), describing time spent practicing debauchery e.g. excessive drinking or using drugs.

In times of unemployment vs traditional methods of wage earning***.

Time spent conforming to society in the ‘‘closet’’.

In times of illness, namely the AIDS crisis.

in times of procrastination/delay as defined by capitalism.

…all of which, by Western societal standards, are seen as ‘‘unproductive’’.

It is unhelpful to reduce the transgender experience to simply a measure against heteronormative time, as the driving factors behind these progressions are inherently different: whilst it may be labelled as ‘‘selfish’’ to exclusively practice sexual acts incapable of producing children, the concept of child-rearing is a political expectation enacted by institutions of capitalism.

(**Childlessness is not exclusive to queer relationships, nor is child rearing exclusive to straight relationships, however the demonisation of infertile (and often older) women throughout history and literature certify that, to society, childlessness is undesirable and not a fulfilling use of womanhood.)

***Even the rise of AI and the subsequent “end of work” discourse align with queer temporality because they challenge the idea that life must follow a linear path of education → career → retirement. The fear that AI will disrupt jobs mirrors anxieties about alternative ways of structuring time—similar to fears about queer and trans people disrupting gendered family structures or workforce participation. Some leftist movements are even embracing a future where work is optional, aligning with queer theorists like José Esteban Muñoz, who argue for utopian futures outside of capitalism’s rigid timelines.

Certainly, Antonio’s life in Lieutenant Nun is riddled with periods of ‘‘unproductive’’ time: violent escapades and imprisonment; time in childless relationships fraternising with multiple women; engaging in excessive drinking and eating with other men.

Despite this ‘’wasted’’ time, Antonio also served as a lieutenant for five years, fulfilling the Colonist Spanish agenda of the 1600s in a time when colonising the new world was not only perceived as a glorified masculine pursuit, but also as a valiant use of time. If Antonio was discovered to be AFAB, however, they would most probably be sent back into the convent where their body could be controlled by the state.

Neither the lifestyle of a nun nor a lieutenant facilitates time pursuing marriage or children. Ironically, Antonio used his life more “productively” (as dictated by the cisgender agenda) when they lived as a man.

Therefore, Antonio escaped heteronormative restraints when they assumed a male identity. They left a space of sexlessness, geographical restraint and religious conformity for freedom in sexual promiscuity, travel and crime. In this choice, Antonio abandoned the traditional, “acceptable” gendered life conforming to biological “duties”, yet instead fulfilled the colonial duties of contemporary Spain.

So, why did I bring up Antonio’s story?

Just as Antonio navigated the world by taking agency over redefining their own identity, the theory of queer temporality encourages us to imagine a future that is not defined by heteronormative expectations.

Transgender time, in particular, is extraordinary in its transformative impact not only on the future, but also on the past. As summarised by Alexander Eastwood, the act of transitioning severs time in a way which ‘induces both relief and grief’: on one hand, enacting their true gender identity provides transgender people hope and security for their future1. However, this temporal shift cannot undo the trauma of experiencing a pre-transitioned past, including a childhood/adolescence ‘lost’ to time.

The privilege of possessing a past and future which have the same gender implications is a feature of the cisgender experience which is unattainable for transgender people.

The Point:

Queer temporality disrupts dominant understandings of time, progress, and success. Whether it’s the rejection of LGBTQ+ history in schools, or the insistence that success must come through traditional pathways, these debates reveal a deep cultural anxiety about non-normative timelines.

Queer temporality is not just about LGBTQ+ identities—it’s about who gets to move through time freely, who is forced to adhere to rigid life scripts, and whose futures are seen as valid.

If you’re interested, check out more media exploring queer time:

Orlando (1992)

Call Me By Your Name (2017)

The Boys in the Band (2020)

As always, thanks for reading!

My pervious post:

Alexander Eastwood, How, Then, Might the Transsexual Read?, Transgender studies quarterly, 2014.